Pier Paolo Pasolini was murdered at around midnight on 2 November 1975. His blood-soaked body was found the next morning on waste ground in Ostia, on the outskirts of Rome, battered so badly the famous face was almost unrecognisable. Italy’s premier intellectual, artist, provocateur, national conscience, homosexual, dead at the age of 53, his scandalous final film still in the editing suite. “Assassinato Pasolini,” the next morning’s papers announced, alongside photographs of the 17-year-old accused of his murder. Everyone knew his taste for working-class hustlers. A hookup gone wrong was the instant verdict.

Some deaths are so suggestive that they become emblematic of a subject, the deceiving lens through which an entire life is forever after read. In this weirdly totalitarian mode of interpretation, Virginia Woolf is always walking towards the Ouse, the river in which she drowned herself. Likewise, Pasolini’s entire body of work is coloured by the seeming fact that he was murdered by a rent boy, the crowning act of a relentlessly high-risk life.

But what if this was the intention; the malevolent cunning with which his assassination was designed? What if, rather than the instant martyrdom of a bullet to the head, Pasolini was killed in such a way as to make it seem that he had sought out his own destruction, a rightful punishment, at least in the eyes of conservatives, for the manifest perversions with which his art as well as life were rife?

Furthermore: what if this reputational as well as actual murder was designed to drown out – contaminate, confuse – the warnings he’d been issuing with increasing ferocity in the final years of his short life? “I know” was the central refrain in a famous essay published a year before his death in Il Corriere della Sera, Italy’s leading newspaper. What Pasolini knew, and what he refused to remain silent about, was the nature of power and corruption during Italy’s brutal 1970s; the so-called “Years of Lead”, named for an epidemic of assassinations and terrorist attacks by both the extreme left and right. What he knew, in short, was that fascism was not over, and that the right would metastasise, returning in a new form to claim power over a populace stupefied by the tawdry blandishments of capitalism. Was Pasolini wrong in his predictions? I think we all know the answer to that.

Pasolini was born in Bologna in 1922, the year that Mussolini became dictator, to a military family. He spent a formative spell in his mother’s home town of Casarsa, in the remote rural region of Friuli, after his father was arrested for gambling debts. The schism between his parents grew more serious as the second world war took hold. Susanna was a schoolteacher who loved literature and art, while Carlo Alberto was an army officer and avowed fascist, who would spend most of the war in Kenya in an English prisoner-of-war camp.

Pasolini studied literature at Bologna University, but when bombing made the city too dangerous he retreated with his mother and younger brother, Guido, to Friuli. He was obsessed with the beauty of the region and its pure, archaic dialect, his mother tongue, spoken by peasants and almost unknown to literature. In 1942, he published his first volume of poems, Poesie a Casarsa, written in dialect. But during the chaotic years of fighting that followed the Italian armistice, not even Friuli was safe. Guido joined the resistance and was executed in the hills by a rival group of partisans, a tragedy that bound Susanna and her adored surviving son even more tightly together.

Part of the allure of Friuli was erotic. It was here Pasolini discovered his sexuality, his magnetic attraction to peasant and street boys. It soon brought him into conflict with authority. In the late 1940s he was charged with corruption of minors because of a supposed sexual act with three teenagers. Though he was later absolved, the scandal drove him and Susanna to move again, this time to Rome.

They stepped straight into the seething city of Bicycle Thieves: a Rome in ruins, its slums populated by a new urban proletariat, escaping the deprivations of the rural south. Pasolini found work as a teacher and immersed himself in another secret language, Romanaccio, the street dialect spoken by the wild youths he befriended. Ragazzi di vita, he called them in the 1955 novel that made his reputation: the boys of life. Pockmarked hustlers and petty thieves, slim-hipped and amoral, often homophobic, nearly always straight. It was these boys he set at the heart of his books, his films, his poems and his life.

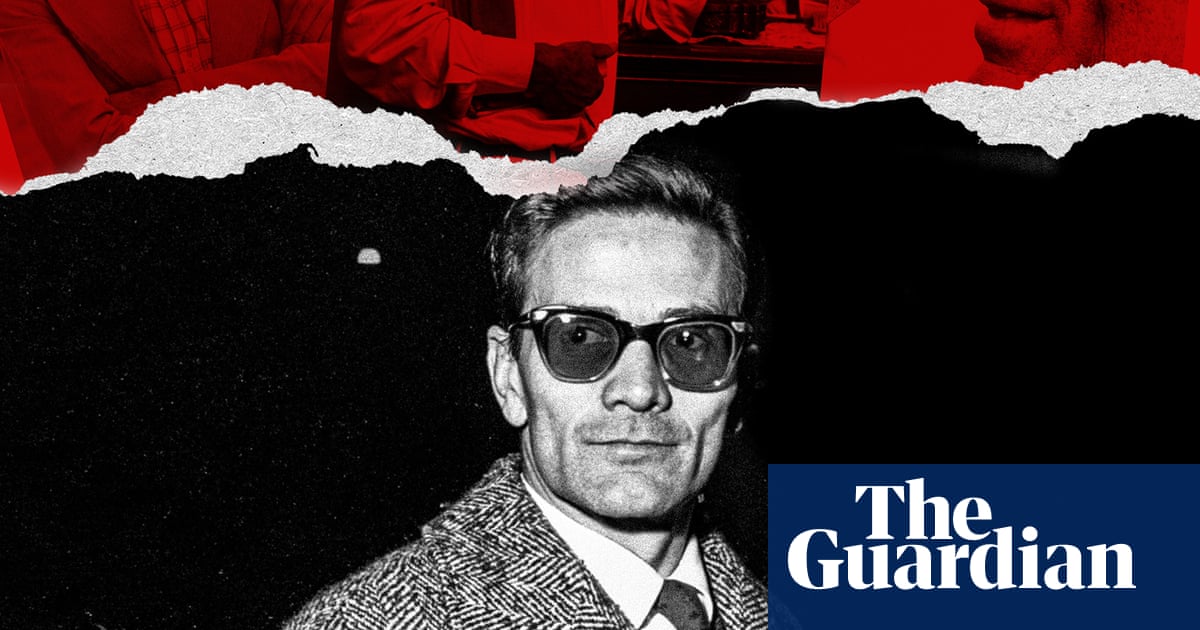

You can glimpse Pasolini in photographs of this period, a slight, slender figure with bandy legs, a mackintosh over his smart suit, dark hair slicked back from an intense, sharp-cheekboned face. A watcher, a driven artist, a passionate football player. He found his way to Cinecittà, the famous Roman movie studio, as a scriptwriter. He assisted Fellini with Nights of Cabiria, and then he was off on his own, writing and directing Accattone, a 1961 neo-realist account of a pimp – played by a real-life street kid, Franco Citti – and his blighted life in a Roman slum.

Lesser artists might have mined that seam for years, but Pasolini soon revealed the exceptional depth and idiosyncrasy of his talent. He made explicitly political films such as Pigsty and Theorem, animated by his loathing for the complacent bourgeoisie. He told the life of Christ in The Gospel According to St Matthew and he took up classical stories too, creating raw and visceral adaptations of Oedipus Rex and Medea, starring Maria Callas, as well as Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, The Decameron by Boccaccio and The Arabian Nights in The Trilogy of Life.

There is nothing in all of cinema like these films, which are bawdy and poetic, visually sublime and heavily invested in the realm of ideas. Many of them star Pasolini’s great love and long-term companion, Ninetto Davoli, a shambling naif from Calabria with an infectiously broad grin. Pasolini’s tendency to use amateur actors gives his films a strange, unsteady realism, as if a Renaissance painting had come to life.

By his 50s, he was globally famous, a controversial figure, constantly under attack. He was tipped for the Nobel prize in literature but had also been subject to 33 trials on trumped-up or invented charges, including public obscenity, contempt of religion and, weirdest of all, attempted robbery; his weapon a black pistol loaded with a golden bullet. Pasolini didn’t even own a gun.

His art was never doctrinaire but it was always political. He’d joined the Communist party in his youth, and was rapidly expelled for his unconcealed homosexuality. He was as often criticised by the left as the right, but though he was a thorn in everybody’s side, he remained allied to communism and the radical left. In the 1970s, he became exceptionally vocal on political matters, using the essays in Il Corriere to discuss industrialisation, corruption, violence, sex and the future of Italy.

In the most famous, published in November 1974 and known in Italy as Io so, or “I know”, he claimed he knew the names of those involved in “a series of coups instituted for the preservation of power”, including the fatal Milan and Brescia bombings. During these Years of Lead, the far right deployed the so-called “strategy of tension” to smear the left and shift the country to a more authoritarian basis. Pasolini believed that among those responsible were figures in the government, the secret service and the church. He referred to a novel he was writing, Petrolio, in which he intended to lay these corruptions bare. “I believe it is unlikely that my ‘novel in progress’ may be wrong, that is to say that it may be disconnected from reality, and that its references to real persons and facts may be inaccurate,” he added.

The last film is the bleakest. No horror film in all the intervening years has come close to Salò (1975), no hacked-up torture porn approaches its icy formal perfection or anguished moral intent. A version of De Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom transposed to the Italian countryside in the final days of the second world war, it is a terrifying masque about fascism and compliance, an accounting of both sides of the totalitarian coin. Like De Sade’s own writing, it’s about power, not pleasure: who possesses it and whom it destroys. It’s an apocalyptic masterpiece that remains unbearable to watch; “off the reservation, proscribed”, as the writer and critic Gary Indiana observed in a screen essay extolling its still-radioactive capacity to wound the viewer.

I set my new novel, The Silver Book, around the making of Salò. I wanted to imagine Pasolini at work, in a tight Missoni sweater and dark glasses, running from scene to scene with the Arriflex camera held lightly at his shoulder, overseeing the construction of turds from crushed biscuits and chocolate for the infamous shit-eating scene. He didn’t bully his collaborators, like Fellini did. He was loved and admired, and also lonely, separate. The compulsive cruising, night after night: in a poem called Solitude he wondered if it was simply a way to be alone.

after newsletter promotion

Ninetto had married two years earlier and the loss had pitched him into total despair, a mood that leaked helplessly into the film. He had publicly repudiated his joyous, erotic Trilogy of Life. Now sex equalled death and pain. As for utopia, no possibility remained. And yet, when an interviewer asked him who was the intended audience for Salò, he said in all seriousness: everyone. He still believed art could perform its counter spell, could shock the populace awake. He hadn’t lost hope.

One of the theories of Pasolini’s death is that he was lured to Ostia to recover some reels of Salò that had been stolen a few months earlier. I took up this story in my novel but I decided not to directly describe Pasolini’s murder, in which he was beaten, his groin shattered, his ear almost severed, before being run over by his own silver Alfa Romeo, causing his heart to burst. The boy who served a decade for his murder had a few tiny spots of blood on him, and no injuries, though he had apparently beaten a man to death. Another sentence from Io so hints at what probably took place: “I know the names of the sombre and important people who lurk behind the tragic youths who chose the suicidal fascist atrocities or the common criminals, Sicilian and otherwise, who offered their services as killers and assassins.”

Pasolini saw what was coming. Like the rarest artists, he had the gift of second sight, which is another way of saying that he paid attention, that he watched and listened and knew how to interpret the signs. On his last afternoon, he was by chance interviewed for La Stampa. A few days after his death, his final recorded words were published in a sold-out issue, a prophecy from beyond the grave.

He talked about how ordinary life was becoming distorted by the desire for possessions, because everyone was taught that “wanting something is a virtue”. He said it affected every aspect of society, though the poor might use a crowbar to get their spoils, while the rich relied on the stock exchange. He said, referring to his nightly excursions into the shadow world of Rome, that he descended into hell and brought back the truth.

What is the truth, the journalist asked. The evidence, Pasolini said, of “a shared, compulsory and wrong education that pushes us to own everything at any price”. He described everyone as victims in this, thinking no doubt of Salò, where victims and perpetrators are locked together in a terrible dance. And he described everyone as guilty, because of their willingness to ignore the costs in favour of their own lucrative private gain. It wasn’t about individual culpability or good and bad actors, he added. It was a totalising system, though unlike in Salò there was a way to escape, to undo the sinister, seductive spell.

As ever, his language was more that of the poet than the politician: dense with metaphor, spooky with warnings. “I go down into hell and I discover things that don’t disturb the peace of others,” he said. “But be careful. Hell is rising towards the rest of you.” Right at the very end of the conversation, it is as if he becomes frustrated by the interviewer’s continued attempts to make him clarify his position. “Everybody knows that I pay for my own experiences in person,” he says. “But there are also my books and my films. Maybe I’m wrong, but I keep on saying that we are all in danger.”

The journalist asks how he thinks he, Pasolini, can avoid this danger. It is getting dark and there is no light on in the room where they are talking. Pasolini says he will think about the question overnight, that he will answer in the morning. But in the morning he is dead.

I think Pasolini was right, and I’m certain that the warnings he kept uttering were why he was killed. He saw the future we’re now in long before anyone else. He saw that capitalism would corrode into fascism, or that fascism would infiltrate and take over capitalism, that what appeared benign and beneficial would corrupt and destroy old forms of life. He knew that compliance and complicity were lethal. He warned about the ecological costs of industrialisation. He foresaw how television would transform politics, though he was dead before Silvio Berlusconi came to power. I do not think the ascent of Trump, a politician formed in Berlusconi’s mould, would have surprised him very much.

He wasn’t perfect. He was infected with nostalgia for a rural peasant Italy, the cost of which he was wilfully blind to. He was against abortion and mass education; he took the side of the French police against the students in 1968. His poetry can be self-indulgent, his paintings are bad. He paid for sex with rent boys who stayed the same age as he grew older, and on the other hand he took them seriously, listened to them, found them work, provided a steady source of support. He was a visionary and an artist of unshakeable moral conviction. He would not shut up.

The timing of his death makes it seem as if Salò was his final, desolate statement but even on his last night he was talking over dinner about his next film. There was more work to come, unimaginable in its shape, unprecedented in its form. He ate steak, he went cruising. He was hungry, you see. He was on the side of life, always.