In 2012, 146 million children were born. That was more than in any prior year. It was also more than in any year since. Millions fewer will be born this year. The year 2012 may well turn out to be the year in which the most humans were ever born—ever as in ever for as long as humanity exists.

Article continues after advertisement

No demographic forecast expects anything else. Decades of research studying Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas tell a clear story of declining birth rates. The fall in global birth rates has lasted centuries. It began before modern contraception and endured through temporary blips like the post-World War II baby boom. For as far back as there are data to document it, the global birth rate has fallen downward—unsteadily, unevenly, but ever downward. So far, falling birth rates have merely slowed the growth in humanity’s numbers. So far.

The view from the top of a Spike

There are quite a lot of people in the world. But that hasn’t been true for long. Ten thousand years ago, there were only about 5 million of us. That’s as many people as today live in the Atlanta metro area, and only a fraction of the number who live in Bangkok, Beijing, or Bogotá. A thousand years ago, our numbers had grown to a quarter billion.

Two centuries ago, we passed 1 billion for the first time. One of every five people who have ever lived was born in the 225 years since 1800. A populous world, on the scale of humanity’s hundred-thousand-year history, is new.

Getting big happened fast. And as soon as it has happened, it’s about to be over. In the shorter run—soon enough to be seen by people alive today—humanity’s global count will peak. There’s a gap between the year of peak births and the year of peak population—a gap that we now live within—because the annual number of births, though falling, has not yet fallen far enough to reach the annual number of deaths. That will happen within decades.

Our times, when many people are alive, may prove to be unlike the entire rest of human history, past and future—if what is normal today persists.

Different experts predict slightly different timetables for when. The demographers at the UN believe it is most likely to happen in the 2080s. The experts at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria place the peak a little sooner in the same decade. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington projects a peak even sooner, in the 2060s.

These dates aren’t exactly the same. But on the timeline of humanity, a difference of twenty years is not really a difference. Each group projects that birth rates will keep falling, so each group projects that we peak this century.

What happens after?

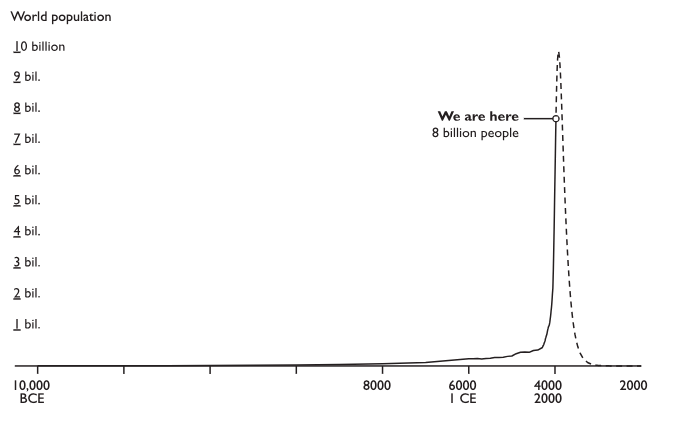

Figure 1.1 plots humanity’s path. We call this picture—of humanity’s past, present, and possible future—the Spike.

We first presented the Spike in a pair of publications in 2023: an opinion article in the New York Times and a matching research paper that filled in the scientific details. We asked: What if birth rates stay on their current course? The answer is that if they do, then humanity will depopulate. We do not mean that humanity would stop growing, reach some plateau, and stabilize near our present numbers. Every decade after turning the corner, there would be fewer of us. Within three hundred years, a peak population of 10 billion could fall below 2 billion.

The Spike is not a product of outlandish imagination. The possibility it charts does not assume some shift or reversal in the way people live and behave. The Spike is what would happen if the whole world one day had the sort of birth rates that are already common in many places. In that future, like now, some people would have a few children. Some would have none. And many would have one or two.

We generated the Spike by projecting a future in which, globally, there were 1.6 children per pair of adults, a statistic that matches the current U.S. average. But, as we’ll show soon, something like the Spike will happen as long as the worldwide average stays below two children per pair of adults. Below two children is what matters, because it means that one generation isn’t replacing itself in the next generation. Is that kind of future likely?

Below-replacement birth rates aren’t special anymore. Already, two-thirds of people live in a country with birth rates too low to sustain their populations over time.

The United States’ average of 1.6 kids is not exceptional. The birth rate is below two in Mexico, Canada, Brazil, Russia, Thailand, and many other countries. The European Union as a whole is at 1.5. The two most populous countries, India and China, are both below two. A birth rate below two is found within each U.S. state; when looking only among U.S. Blacks, whites, or Hispanics; and in every Canadian province.

What’s normal now, around the world?

You stand now at the top of the Spike with 8 billion others. The story of the future starts with understanding the fact that most of those 8 billion others don’t (or didn’t, or won’t, once they grow up) aspire to parent very many children.

One of those people is Preeti. In 2022, Preeti had a baby in a crowded government hospital in India. Her baby was born very small. So after a nurse rolled up a cart to weigh and assess her baby girl, Preeti was brought to the hospital’s new program for underweight newborns, called “Kangaroo Mother Care.” Preeti and her baby were assigned one of the program’s ten beds in the next room.

Preeti lives in Uttar Pradesh, a populous, poor state in the north of India. She traveled to the hospital from a half-mud, half-brick home in a small village. The nurses down the hall don’t have neonatal incubators, which are the standard treatment for underweight babies born in the rich places of the world. But they do have proven, low-cost procedures to keep tiny babies warm, fed, and alive.

The baby was Preeti’s first. She expects to have one more. She already loves this girl. But it would be good, Preeti says, if the next one were a boy so she can “get the operation”—meaning sterilization surgery, having done her duty to have a boy.

Preeti’s hope for two children is normal now, even in a poor, disadvantaged state in India. This book tells her story and her nurses’ stories. Their choices, their lives, are also part of a wider story. A story in which women in rural Uttar Pradesh (where many women are poor, haven’t had much schooling, and marry young) choose two children is a story in which many women, everywhere, choose even fewer. Preeti is one eight-billionth of the story that this book tells: Choosing fewer children is becoming normal, everywhere.

Rural India might seem like the middle of nowhere to someone who has never been to Uttar Pradesh. But to an economist or demographer, India is in the middle of the world’s statistics: middle in income, middle in life expectancy, and middle in birth rates. And what happens in India is important for the planet as a whole. At some point between when Preeti’s baby was born and now, India became the world’s most populous country. If there’s one thing that many non-Indians know about India, it’s that there are a lot of people there: in 2025, 1.4 billion.

What fewer people realize is that India is on a path to a shrinking population, which is a corner that China has recently turned and Japan did in 2010. That’s because many women like Preeti plan to have one or two children. In the most recent national data from India, women were having children at an average rate of two per two adults. Because that data point was from 2020, the average has almost certainly fallen to a little bit less than two by 2025. But even back in 2020, those who had been to secondary school (a growing fraction of girls and women in India) averaged 1.8, which matches the average for all U.S. women in 2016. The hospital where Preeti gave birth is in an especially disadvantaged state of India. But young women there said that they want about 1.9 children, on average. Small families are the new normal.

What’s so normal about normal?

For many people, a society where women average 1.8 or 1.9 children would feel familiar. But so much familiarity is deceiving.

Normalcy will create something unprecedented. Birth rates that are normal in most countries today will lead to an unfamiliar future of global depopulation.

If today’s normal stays normal, then big changes are coming.

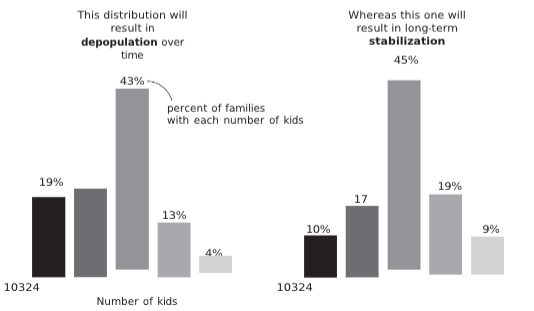

And yet, looking around, you might not notice the difference between a society on the track toward depopulation and one headed for a stable future. Figure 1.2 diagrams two (of many) possible futures, with different fractions of people choosing zero, one, two, three, or four children. The taller a bar is, the larger the fraction of adults who have that many children. On the right is a distribution of family sizes that would make for a stabilized population, neither growing nor shrinking. On the left is a depopulating future, with 1.6 births per two adults, on average.

How different are the left and the right? It depends on what we’re asking. The bars look only a little different, but their consequences are very different. Their implications are as different as a steady, stable global population, on the right, and a decline toward zero, on the left. The next chapter will trace out the arithmetic (painlessly), so you can see why for yourself. But here is our point for now: They don’t look that different. Both include some families with a few children, plenty with none or one, and a bunch with two. Both look pretty ordinary if you live in a place like Austin, Texas, where we do. Professional statisticians could tell the difference, if they had all the data. But could you tell the difference on a visit to the park, the grocery store, the pool? Could you see the difference at school drop-off, at the coffee shop, or jogging around the lake? Probably not. And that means the patterns of family life leading to a profoundly different future can slip past our notice.

We may not feel it. We may not see it. But we teeter at the tip of the Spike. Our times, when many people are alive, may prove to be unlike the entire rest of human history, past and future—if what is normal today persists.

Is this story four-fifths over?

Birth rates around the world vary in interesting ways: across countries and provinces, by race and religion, by education and income. In the United States, teen births are most likely to happen in January, but births to married moms are most likely in May. In India, Dalits—the disadvantaged caste group formerly called “untouchable”—tend to have slightly more children than people born into more privileged castes. The varied history is fascinating, too: France’s fertility fell fast in the 1700s, long before its neighbors’ did and long before hormonal birth control or latex condoms were invented. Experts have written thousands of articles about the details in scholarly journals. But those detailed differences don’t help us understand what is likely to happen. We learn what is likely to happen by seeing what people around the world have in common. Every region on Earth today either has low birth rates, like China, India, or the United States (the three most populous countries), or has falling birth rates, like most African countries. If humanity stays the course it is now on, then humanity’s story would be mostly written. About four-fifths written, in fact. Why four-fifths? Today, 120 billion births have already happened, counting back to the beginning of humanity as a species, and including the births of the 8 billion people alive today. If we follow the path of the Spike, then fewer than 150 billion births would ever happen. That is because each future generation would become smaller than the last until our numbers get very small.

Right about now it would be understandable to think, “But come on! This is all too much confidence about an unsustainable trend! Surely people won’t keep having fewer and fewer children forever.”

Some trends are indeed unsustainable, and it would be a mistake to extrapolate them indefinitely. We’re not making that kind of mistake here. People around the world could continue to have small families. Not smaller than today. Small like today. They could continue, for a long time, to make individual decisions that add up to 1.4 or 1.6 or 1.8 children on average. A depopulating future would arise from steady birth rates at these levels.

How long depopulation could continue depends on what people choose. Our numbers will fall decade by decade, as long as people look around and decide that small families work best for them. That’s all it would take. There would never be more than 150 billion humans, if families continue to have a bit less than two children each, on average. So if—if—humanity stays this course, then there would be only 30 billion more of us for the rest of human history. How exactly might we fizzle out in that future? Should anyone literally expect that humanity will depopulate down to the last two people?

No. In a world that sheds 8 billion people, something big would eventually break and knock us off this path, for good or for bad. We would not ride the precise math of the Spike down to the last few million of us.

The off-ramp from the Spike could be sharply down. The end could be some catastrophe that a larger population might have survived but a smaller population couldn’t. We have a chapter about this possibility. Or the off-ramp could be up. Maybe birth rates would rebound, after a disaster or disintegration that staggers us. How? If progress halts or reverses, if life becomes worse, then it would be like we moved toward humanity’s poorer past. People had more babies in the poorer past than they do today and tend to have more babies in poorer countries than in richer countries. So perhaps the off-ramp is some disaster that regresses on social, technological, or political progress, knocking backward humanity’s millennia-long history of struggle and growth.

That might mean higher birth rates, and it might even stabilize the population, but it wouldn’t be good.

Might matters reverse automatically, without big changes? The short answer is that that’s unlikely. A reversal would break a centuries-old trend of declining birth rates. That trend is founded on social and economic changes that most of us view as progress and that none of us should expect to disappear.

We can learn about the odds of an automatic rebound from the histories of countries where birth rates have fallen low. Since 1950, there have been twenty-six countries, among those with good enough statistics to know, where the number of births has ever fallen below 1.9 births in the average woman’s full childbearing lifetime.

All of us alive and working today are decades away from anyone having all the answers we need. But that does not exempt us from facing up to the facts.

Never, in any one of these twenty-six countries, has the lifetime birth rate again risen to a level high enough to stabilize the population. Not in Canada, not in Japan, not in Scotland, not in Taiwan. Not for people born in any year. In some of these countries, governments believe they have policies to promote and support parenting. But all of them continue to have birth rates below two. A 0-for-26 record does not mean that things couldn’t change, but it would be reckless to ignore the data. If a reversal happens, it will be because people decided they wanted to reverse it and then worked to make it happen, not because automatic stabilizers kicked in.

It takes two (to ever have a stable global population of any size)

Perhaps even at the end of this book you will not agree that a world of 5 billion flourishing people could be better than a world of 500 million equally well-off people. But do you think the size of the population should ever stabilize at any level—even a level much smaller than today’s—rather than dwindling toward zero?

Some inescapable math. For stabilization to ever happen at any level—even to maintain a tiny, stable global population—the same math applies: For every two adults, there must be about two children, generation after generation.

Wait, two? Exactly 2.0? Two for everybody? No, the next chapter explains. For now, it is enough to see that any population, large or small or tiny, continues to shrink if there aren’t at least two children for each two adults. Dwindling toward zero is neither balance nor sustainability.

Notice what this inescapable math implies: Once the global average falls below two, which is a marker that we are likely to pass in a few decades, stabilizing the world population would require the global birth rate to increase and then to stay higher permanently. That has never happened before in recorded demography.

Maybe you feel confident that someday, somebody good and powerful will figure it out. Maybe you are more optimistic than the projections in the Spike that, after some decades or centuries of depopulation, humanity will manage to pull its birth rates back up to two. Even if you think so, read on.

For one, you might be wrong. This book will show that some popular beliefs about the history of how governments and movements have shaped birth rates are wrong.

For another, even if the global population will eventually recover, it makes a big difference when the recovery begins. Here are the stakes, even in the optimistic case of an unprecedented recovery: Each decade of delay in starting the rebound causes the final, stabilized population size to be 8 percent smaller, ever after.

It is time to pay attention

Do you remember when you first understood that climate change is a seriously big deal? Most of us born before 1990 went through school without much awareness. Your authors grew up in a time when school-children learned about the problems of an ozone hole, acid rain, and depleted tungsten supplies, not carbon emissions. The first book about climate change for a general audience, Bill McKibben’s The End of Nature, was not published until 1989. But the basic facts have been known for a lot longer than the social movement has been around. Congress heard scientific testimony in the 1950s. In 1965, President Johnson included in a speech to Congress that: “This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through radioactive materials and a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels.” That year, the White House released a report calling carbon dioxide a pollutant. Progress, such as it is, has only accelerated in recent years. But somebody got started in the 1950s.

Good thing they did, or the climate policy of today would not have the tools, the technologies, and the political awareness to make the progress it is finally making. Scientists in the 1950s and ’60s had recognized the threat of climate change. They did not have a complete map to every solution. But they did not believe it was too early to get started, six decades ago.

The tip of the Spike may be six decades from today. (Or a few decades sooner than that.) Like the climate pioneers of the 1950s, all of us alive and working today are decades away from anyone having all the answers we need. But that does not exempt us from facing up to the facts. It’s time to start learning. The first step is understanding the population today, where it came from, and where it is heading.

__________________________________

Excerpted from After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso. Copyright © 2025 by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.