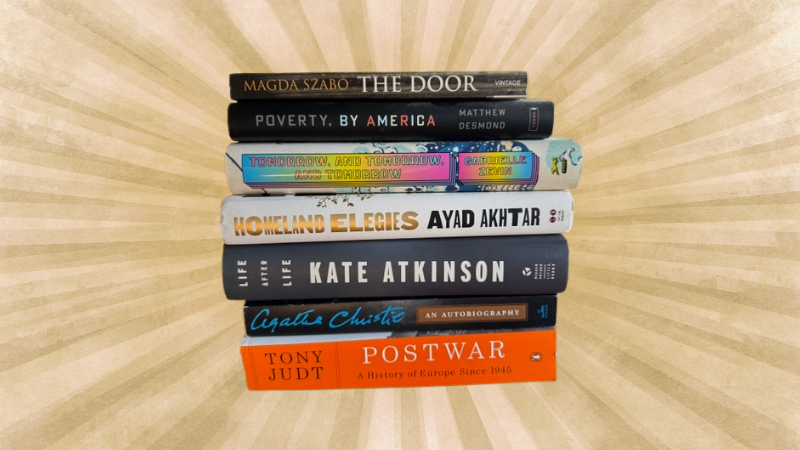

Featuring Gabrielle Zevin, Kate Atkinson, Matthew Desmond, and More

About a decade ago, my bedroom was kitty corner to Susan Orlean’s—the iconic New Yorker writer and (years later) viral peak-COVID tweeter. I was at a residency scribbling poems, Orlean mapping out The Library Book. An article Orlean had written years before was still stuck in my mind as she had nearly convinced me to get urban chickens.

“People loved that one!” she said, a little bewildered over its magic, when I brought up how she almost changed my life into one defined by chickenfeed and avoiding racoons. In Orlean’s memoir, Joyride, she talks about her pet chickens, how her favorite fell sick and ultimately had to be put down. Anyone who has been in a similar scenario knows the scene: crying in the waiting room, alone, bald in your public display of grief. A woman with a pet came over to Orlean to comfort her. “Oh, honey, I’m sorry,” she said. “Was it your dog?” Orlean: “‘No,’ I sobbed, my face in my hands, ‘it was my chicken.’”

Joyride traces the life of a writer who perhaps is best known outside the literary world for Meryl Streep playing a fictionalized version of her in Spike Jonze’s Adaptation but known within it for the original text that inspired it, The Orchid Thief, among other titles. Yet premier are her essays that dive into everyday habits and people and reveals their sparkle. The chicken scene generally captures the way Orlean can cast a thoughtful eye over her life’s experiences and still manage to be funny while not dismissing the darts life threw at her.

Through the pages of Joyride, Orlean describes how she adeptly elbowed her way into writing gigs armed with little more than palpable curiosity, sheer will, and certainty of her future as a writer. After a humble start post-college, like any good journalist, Orlean knew to keep chasing opportunities to see what she might catch.

She asks the editor of The Village Voice if she might cover Rajneesh and his commune in western Oregon; she asks for a contract at The New Yorker when most might count their blessings for the gentleman’s agreement she had. Orlean’s writing about Rajneeshpuram catapulted her to the national stage and led to calls from venues like Glamour and Vogue. She became a New Yorker staff writer in a few years.

Despite the rat race, Orlean never loses sight of her love of the craft. “Every sentence is a slippery invention, a bit of quicksilver I released to the world,” she says, “and then it’s time to amend the next one. That’s why being a writer is never boring, that’s also why it’s always a little terrifying.”

It’s hard not to read some of Joyride, for this reader anyway, as a paean for a time in which someone could scrape pennies and pay rent in a city. (Okay, Portland—but also, Portland!). Today it feels near-impossible to chase dreams in the way Orlean does in these pages: on a hope and a prayer, with a steel will keeping her going. And what such chasing led to such a remarkable writer! Here’s hoping for a future in which pursuing the uncertain feels feasible again.

Orlean tells us about her to-read pile: “I like a nightstand stack that mixes the old and the new, pleasure and work. I’m beginning to research a new book project, so a few of these books are part of that process. But what I crave before bed is great writing, something that can envelope me with gorgeous language and transport me. I lean towards fiction, but a brilliant work of nonfiction can be just as transporting. I like being lifted into another world before I surrender to sleep.”

*

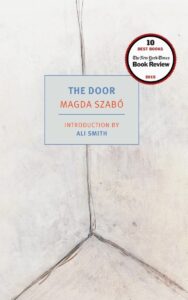

Magda Szabó, The Door (tr. Len Rix)

“It’s astonishing that this masterpiece should have been essentially unknown to English-language readers for so long,” writes Claire Messud in the New York Times, “a realization that raises once again the question of what other gems we’re missing out on. The dismaying discussion of how little translated work is available in the United States must wait for another venue; suffice it to say that I’ve been haunted by this novel. Szabo’s lines and images come to my mind unexpectedly, and with them powerful emotions. It has altered the way I understand my own life.” Honestly, I agree. I loved this novel so much I bought it for half a dozen people once I was finished.

Matthew Desmond, Poverty, By America

This Pulitzer-winning book on how poverty continues to define this country. “18 million families in the U.S. live under the deep-poverty metric of $13,100,” writes J. Howard Rosier at Vulture. “But focusing on these statistics obfuscates what is in effect a moral argument. Desmond’s great contribution to the topic is asking why we as a society are willing to accept this. His answer — that it is in most people’s economic interest to accept economic arrangements that keep people poor — is likely to roil the classic debates about personal responsibility.”

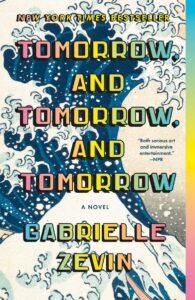

Gabrielle Zevin, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow

In its starred review, Kirkus describes how two gamer friends find each other during college in Zevin’s novel. “They determine that they both still game, and before long they’re spending the summer writing a soon-to-be-famous game together in the apartment that belongs to Sam’s roommate, the gorgeous, wealthy acting student Marx Watanabe. Marx becomes the third corner of their triangle, and decades of action ensue, much of it set in Los Angeles, some in the virtual realm, all of it riveting. A lifelong gamer herself, Zevin has written the book she was born to write, a love letter to every aspect of gaming.”

Ayad Akhtar, Homeland Elegies

Lopamudra Basu writes at World Literature Today of the Pulitzer-prize winning playwright’s first novel in years, “This experimental novel is simultaneously a poignant reflection of the complexities of being a Muslim writer in post-9/11 America…Historical events like 9/11, the truck bomber in New York, and the rise of Donald Trump form the historical landmarks against which intense dramas of his personal and familial history are played out. In lieu of a plot, this novel follows an episodic structure, woven with many metafictional commentaries, dreams, diatribes, and debates about the critical reception of his works.”

Kate Atkinson, Life After Life

At The Guardian, Alex Clark calls Life After Life “a great big confidence trick – but one that invites the reader to take part in the deception.” She goes on: “Every time you attempt to lose yourself in the story of Ursula Todd, a child born in affluent and comparatively happy circumstances on 11 February 1910, it simply stops.” At the beginning, Ursula is born, but the doctor is cut off because of snow. She is born with her umbilical cord around her neck and does not survive. Start again. The doctor arrives—and saves her life. The story continues.

Agatha Christie, An Autobiography

I didn’t realize the Queen of Crime holds the crown for bestselling fiction writer in history with over two billion—with a B—copies of her works sold. While of course I can find a review of the book, I kind of love the breakdown I found of how much real estate Christie gives to important moments in her life in this doorstop of an autobiography. A year defined by loss and difficulty (her beloved mother’s death, Christie’s breakdown, her husband’s philandering ending their marriage) gets about seven pages. Twenty years—and not just any twenty, but 1945-1965—elapse in a speedy 23 pages!

Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945

“This is the best history we have of Europe in the postwar period and not likely to be surpassed for many years.” in Publishers Weekly in its starred review. “Here Judt combines deep knowledge with a sharply honed style and an eye for the expressive detail. Postwar is a hefty volume, and there are places where the details might overwhelm some readers. But the reward is always there: after pages on cabinet shuffles in some small country, or endless diplomatic negotiations concerning the fate of Germany or moves toward the European Union, the reader is snapped back to attention by insightful analysis and excellent writing.”