Scientific fieldwork is an integral part of research in many disciplines, including geology, geography, forestry, ecology, and others. Researchers use the outdoors as a natural laboratory, measuring snowpack and glacier movement, tree growth and wildfire spread, and everything in between. When anthropologist Jane Goodall studied chimpanzees in Tanzania, she was doing fieldwork. When Parks Canada archaeologists worked with Inuit in Canada’s Arctic to find the wreck of one of Sir John Franklin’s ships, the HMS Erebus, they were doing fieldwork. When University of Alberta glaciologist Dr. Alison Criscitiello collected an ice core from the summit of Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak, she was doing fieldwork.

Article continues after advertisement

But it’s not just research scientists who do fieldwork. Anyone can participate in community science, which involves working on a local research project run by scientists who rely on volunteers to collect more data points than they could on their own. North America’s longest running community science project started in 1900: the annual Christmas Bird Count. On a single day sometime between December 14 and January 5, birders come out in droves to observe and count birds in a twenty-four-kilometer diameter circle in their region—the same circle every year. They submit their findings to the national coordinator who collates their results. Another example of ecologically focused community science is the BioBlitz, a concept that started in 1996 and involves volunteers in an intensive one-day inventory of all species in a defined area.

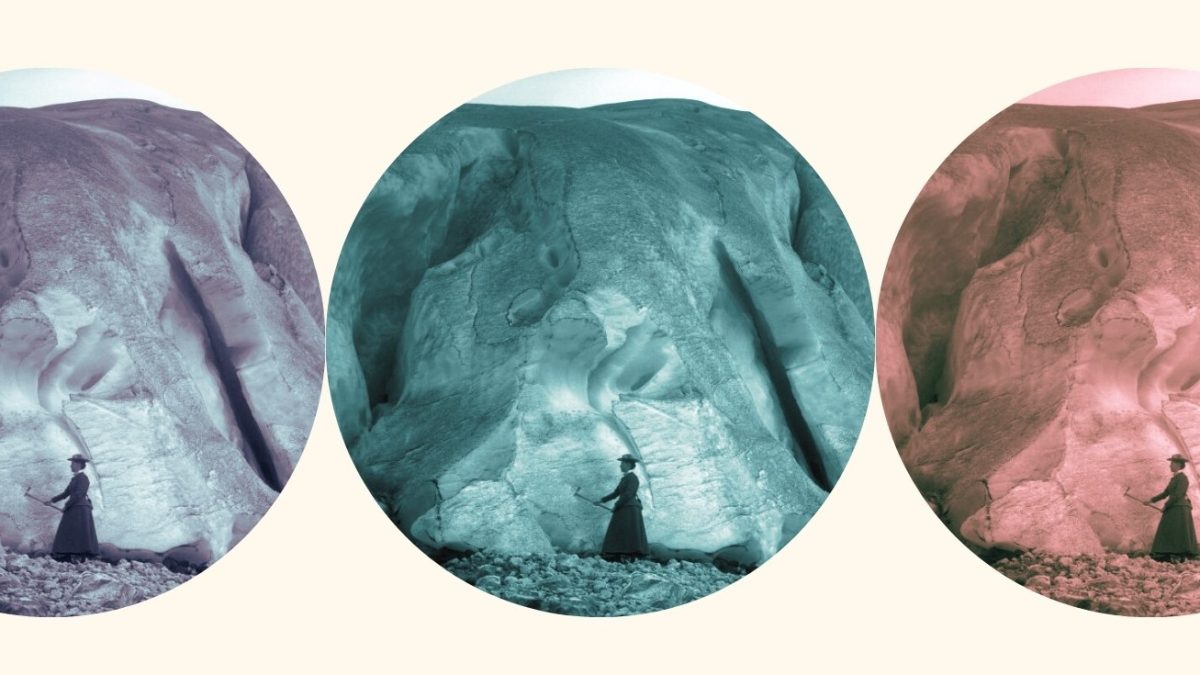

Many women went before me, in both field science and outdoor exploration, in an era when women weren’t “supposed” to be field researchers.

What all fieldwork projects have in common is that they require working outside, whether that’s in your own neighborhood or on a remote glacier. For community science projects, there’s a leader who explains what data you have to collect and what methods to use. For your own field research, you have to decide what needs to be measured and how. Both require flexibility and patience, and sometimes dealing with the discomfort of bad weather, insects, heavy backpacks, malfunctioning equipment, and even boredom. Remote fieldwork, in particular, requires tackling a range of mental, physical, and logistical challenges. Field researchers thrive on a specific set of skills and attributes: resilience, self-reliance, creative problem-solving, and the ability to focus on the moment to decide what needs to be done.

In a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, cartographers were so exacting about their science that they ended up creating a map at the same scale as the world itself. We can’t do that. If we could measure everything, we’d have reams of data but not enough human power or computer power to analyze it. In environmental science, field research is often used to measure small-scale processes and then scale them up using numerical models (computer models that use field data as input) or remote sensing (satellite data analysis, lidar measurements). Field research can also be used in the opposite direction: to ground-truth the output from numerical models and remote sensing analyses. Small-scale research provides a sense of how larger-scale processes work, which are much more difficult to measure. Researchers set up experiments in natural systems by first identifying what their research questions are. The trick lies in determining the best variables to measure or monitor to answer those questions.

In many university programs, attending a field school is a required part of earning a degree, especially in geology, forestry, archaeology, and geography. Students are immersed in the outdoors for a short, intensive period, during which they learn field skills applicable to their discipline, like how to measure river flow or tree growth. Everyone learns the same things in the same environment and works together to complete their field projects. Students often live together in field camps for up to ten days at a time. They eat meals together, conduct their research together, and socialize in the evenings—either doing homework or hanging out around a campfire.

This combination of working and living together creates a camaraderie that forges strong bonds of friendship and belonging, and can be especially important for the success of historically marginalized people in academia. Studies have shown that students who participate in field schools have higher graduation rates and higher graduating GPAs, suggesting that these experiences could be a way to enhance diversity in science by increasing access for women and other underrepresented groups. For me, field school changed my career trajectory: I went from potentially dropping out of university to sticking around for a fun and interesting outdoors course.

Fieldwork played a big part in making me who I am today. Many women went before me, in both field science and outdoor exploration, in an era when women weren’t “supposed” to be field researchers. Some of these trailblazers include Americans Mary Schäffer-Warren, Mary Vaux, and Canadian Phyllis Munday.

In the early 1900s, society assumed that being outdoors “would have little appeal to the average woman whose time is divided between her dressmaker’s, her clubs and the management of her maids.” But Mary Schäffer scoffed at this description, saying, “We can starve as well as men; the [bogs] will be no softer for us than for them; the ground will be no harder to sleep upon; the water no deeper to swim, nor the bath colder if we fall in.” She was adamant that she enjoyed her outdoor adventures, and there was no reason those adventures should be limited to men. Mary Vaux was equally enamored with mountains over society, writing that “golf is a fine game, but can it compare with a day on the trail, or a scramble over the glacier, or even with a quiet day in camp[?]…Somehow when once this wild spirit enters the blood…I can hardly wait to be off again.”

I felt a kinship with Schäffer, who was commissioned by the federal government to survey Maligne Lake in 1911, despite having no experience with surveying. She used a spool of measuring tape to determine the distance between survey points, but it fell into the lake and a new one was ordered from Toronto. She promptly dropped the replacement spool into the lake as well, but managed to have Arthur O. Wheeler, who had brought her the replacement spool, retrieve it so she could continue her work. Then she experienced problems with a piece of metal in her wooden survey tripod, which affected her measurements for the worse, so she had to switch to using a piece of wood instead. Despite these setbacks—just like I’d had to deal with in the field—Schäffer persevered in surveying the lake and naming local peaks for friends and colleagues, including Mary Vaux. She submitted her survey data and place names to the National Geographical Board in Ottawa, where they were accepted and included on new maps of the area.

Vaux first visited Glacier House in 1887, the year the hotel opened. She, her father, and brothers are credited with recording the first measurements of glacier change in the Selkirk Mountains. They photographed the nearby Illecillewaet Glacier before heading back to Philadelphia, then returned in 1894 to take new photos. Their images showed that the glacier had retreated significantly in the seven years since their last visit. This kicked off a family legacy of annual glaciology measurements at Illecillewaet, Asulkan, Yoho, Victoria, and Wenkchemna Glaciers, which started in 1896 and ended in 1922. The family selected landmarks around each glacier from which they took compass bearings of the ice and surrounding peaks, they made sketches of each glacier, and took repeat photos from set photographic points using heavy large-format cameras with glass plates. They also set up metal plates on each glacier’s snout that they surveyed from a fixed point to measure annual glacier flow rates. These plates had to be moved regularly as the glaciers continued to retreat.

Vaux took on her family’s annual glacier measurements in 1911 and continued them on and off until 1922, after which her work was continued by surveyor Arthur O. Wheeler, who’d helped her with previous glacier surveys. Her scientific work was recognized when she was elected a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, one of few women to receive that honor, and she served as president of the Society of Woman Geographers. I felt a kinship with Vaux, taking her measurements of Illecillewaet and other glaciers. I was immersed in the same kind of landscape that she explored: the rocky terrain of the proglacial zone, with the constant sound of rushing water and an ever-retreating glacier snout, but I was studying water flow instead of ice flow. I wondered if Vaux missed glacier surveying when she gave it up after 1922, or if she felt that she had come to the end of a family era.

Schäffer and Vaux were early examples of what women could be and do in rugged landscapes at a time when gender roles were highly circumscribed by society. They forged a path for future women and girls to become explorers, mountaineers, and scientists, through their pioneering trips in mountainous regions. Though they often had male guides or a husband with them, they were particularly independent and tough-minded: they knew what they wanted and set out to achieve it. They served as historical mentors for me: adventurous women in an era when women most often stayed at home; strong women who bucked social conventions and did so without apology.

*

Some couples can’t work together, but my husband and I have worked in the field with each other since my first research project back in 1998. We have a strong partnership that can weather the challenges of fieldwork, and each of us often know what the other is thinking, or going to say, before they even say it. Our relationship brings to mind explorer Phyllis Munday who, along with her husband Don, climbed many peaks in the southern Coast Mountains and elsewhere across British Columbia between the 1910s and the 1940s.

Phyllis was an outdoors person from a young age, a tomboy who enjoyed daring exploits like crossing deep ravines by walking on logs that spanned their depths. After her family moved from Nelson to Vancouver, Phyllis spent her spare time climbing Grouse Mountain on the city’s North Shore. Phyllis met Don when she was twenty-four, at a military hospital in Vancouver where she volunteered as a nurse. He was also a climber, though he had injured his left arm in the war and was somewhat limited by this disability. They climbed together regularly as members of the BC Mountaineering Club, and married in 1920. In 1921 they had a daughter, Edith, and eventually moved to North Vancouver for her schooling. But they kept climbing the southern Coast Mountains in their backyard.

The Mundays also climbed on Vancouver Island. As the story goes, they were standing on Mount Arrowsmith near Port Alberni, looking across the Strait of Georgia, when they spotted a massive peak on the mainland. It rose well above the adjacent peaks in the southern Coast Mountains, and they only glimpsed it for a moment before it was once again wreathed in cloud. They got a quick compass bearing ahead of its disappearance, however, and named it Mystery Mountain; the couple would dedicate the next twelve years of their summer travels to finding and summiting it.

They tried several routes up various coastal fiords before settling on Knight Inlet as the best way to reach the glaciers of the southern Coast Mountains and Mystery Mountain itself. They attempted to summit the mountain (named Mount Waddington in 1927), the highest peak in the Coast Mountains, sixteen times, and came close to succeeding on several occasions. Sometimes they were thwarted by weather, other times by food running out, and once by not having enough pitons and rope. The expeditions weren’t all failures, however, as they made first summits of many nearby peaks on days they couldn’t access Waddington. And when they returned from their Waddington trips, there was always the Alpine Club of Canada summer camp to attend, where they may have rubbed shoulders with Elizabeth Parker, the woman who co-founded the club and for whom Parker Ridge in the Rockies is named.

Mary Schaffer, Mary Vaux, and Phyllis Munday epitomized my field ethic. In them, I found century-old kindred spirits.

The Mundays weren’t just mountaineers, they were also scientists. They took compass bearings, field notes, and panoramic photos of the areas in which they climbed, areas that were virtually unknown to white settlers. They used their data to make detailed photo-topographical maps of the new terrain they had explored, opening up the area to future adventurers. They wrote articles for the Canadian Alpine Journal (for which Phyllis served as editor from 1953 to 1969), outlining the peaks they’d seen and climbed, and providing elevations and names for others. More thorough records of their climbs can be found in Don’s book The Unknown Mountain, in which he recounts their expeditions to reach Mount Waddington.

While Phyllis did much of the scientific work without recognition (common for women at the time), Don belonged to a number of scientific organizations, including the International Commission on Snow and Glaciers. It’s unclear if Phyllis’s contributions were shared with these organizations, or if they were assumed to be solely Don’s work. Phyllis also assisted the Royal BC Museum, preserving insects for them that she and Don gathered on their travels. She found that “collecting and mapping made [us] see and observe a lot of things that [we] might have missed otherwise.” This was exactly what I had learned at field school: to do science in the mountains I had to look carefully at the landscape and observe the environment at work, seeing things that I might not notice otherwise.

Phyllis and Don described themselves as “a climbing unit something more than the sum of [their] worth apart.” This was partly because of Don’s injury; he sometimes needed assistance from Phyllis on tricky parts of climbs. Don wrote, “we relied on each other for rightness of action in emergencies, often without audible language between us,” and “my wife and I bring to this…travel a glad confidence in each other that one not knowing us well might brand foolhardiness.” This was why their relationship made me think of mine with Dave: like the Mundays, we were a pair working together to travel through and document mountain landscapes.

Phyllis was a revolutionary woman who summited many peaks in many different locations. Her accomplishments and contributions to mountaineering were recognized with a wide variety of honors, including the Alpine Club of Canada’s Silver Rope Award in 1948 for climbing leadership, and their badge for outstanding service in 1970. She was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1973, and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Victoria in 1983.

I understood Phyllis’s enjoyment of the outdoors. She wrote, “on a mountain you are so very close to nature…I always feel a friendship with mountains, almost as if they were human.” I felt the same thing when I was in the field: a friendship with the peaks that surrounded me, even if I wasn’t planning to summit them. While I didn’t want to become a climber, I shared her passion for the mountains, her scientific observations of those landscapes, and her connection with her partner, all of which made fieldwork so important to me.

These three women were instrumental in my development as a field scientist in the mountains, their stories were liberating and adventurous. I hoped to be like them: fearless and undaunted by the tasks ahead of them. From surveying lakes to measuring glaciers to collecting insects and mapping new peaks, these women were heavily involved in scientific fieldwork, in an era when women didn’t do that sort of thing. They were expected to do “easy” things like botany (see Erin Zimmerman’s Unrooted: Botany, Motherhood, and the Fight to Save an Old Science). But even botany became “professionalized,” with women’s work seen as inferior to that of men. Mary Schaffer, Mary Vaux, and Phyllis Munday epitomized my field ethic. In them, I found century-old kindred spirits.

__________________________________

From Meltdown: The Making and Breaking of a Field Scientist by Sarah Boon. Copyright © 2025. Available from University of Alberta Press. Featured image: Mary Vaux at Illecillewaet Glacier, 1898.