Like many women I know, I’ve wasted good amount of my time on Earth trying to be likable. I’ve sat quietly, apologized for my presence, dressed for the male gaze. I’ve tiptoed around men who offended me and said thank you when I really meant go away.

Article continues after advertisement

For years, this performance of likability followed me everywhere—even into my writing. If a beta reader so much as hinted that my protagonist was unlikable, I’d rewrite her immediately. Unlikable is, after all, the very worst thing a (female) character can be. All the one-star reviews on Goodreads say so. Readers can’t stand them, won’t connect with them, troll them and pan them. No one wants to spend thirty dollars or 300 pages with a nasty woman.

I was working on what would end up being my debut novel during the politically fraught time around the 2020 election, which coincided with the emotionally fraught time of my early forties. I already had one novel fail to sell on submission a few years earlier. I was eager for this one to be different. I wanted a new agent and a six-figure publishing contract. Most of all, I wanted readers. My plan was to do everything right this time. I’d make readers love my characters, especially my main character, who I spent countless hours buffing to a shine—excising her political ideologies and her cloying needs and her abrasive dialogue. Anything too anything had to go. My character would not offend. She would be neutral. And everyone would like her.

My character may have been right all along, but she never changed, and so she never changed her world.

Right?

As it turned out, no. Rather than being likable, my character was a one-dimensional tryhard. Sure, she had a desire—she was an artist and craved recognition for her talent—but she didn’t pursue that desire. Instead, she was pursued upon. She spent the course the manuscript adapting to or reacting to things that happened to her, usually by (male) characters who were morally grayer, and thus more interesting. My protagonist became less and less of a subject, more and more of a direct object. A thing handled. A device to be used. On the page, she barely painted. She fumed at her stasis, but silently, stoically. She was so afraid of making mistakes, she let others make them for her. In this iteration of my book, my character may have been right all along, but she never changed, and so she never changed her world.

She was, in other words, unreadably boring.

Frustrated, I shoved my manuscript in a drawer and attended to a reading binge; for months, I found myself drawn almost exclusively to female-centered thrillers. I read (or re-read) books like White Ivy, Gone Girl, Pretty Objects, Luckiest Girl Alive, Social Creature, Eileen, My Sister the Serial Killer, Give Me Your Hand, The Lost Night—and what jumped out at me was that the joy I felt reading these books came, in the most literal sense, from the unlikable female characters. They were murderers and popinjays, strivers, cheaters, liars, petty criminals, and Machiavellian party girls. They acted from their id and made terrible decisions. They were selfish and sometimes repulsive. Often I was goggled-eyed at their brazenness or folly. Still, I was hooked. I flipped pages as quickly as I could because I was hungry to see what these “awful” people would do next. I was hungry to see them exert whatever power they had over the forces that had sought to stop them.

Despite their unlikability, I was rooting for them.

Why?

The answer, I think, has to do with psychology. From an evolutionary standpoint, humans crave stories because they teach us something about how to behave. From a psychological standpoint, we crave ‘bad-guy’ stories because they allow us to confront our darkest, most hidden desires—what Carl Jung called our “shadow selves.” Giving us a nasty woman protagonist allows us access into her brain, and thus allows us to explore, from a safe distance, a certain kind of wish fulfillment.

It is perhaps no wonder, then, that I craved these kinds of stories in 2020 when COVID had trapped me inside to homeschool my three children, when Ruth Bader Ginsburg had died and conservatives gained full control of the Supreme Court, when Trump was devoted to undermining the entire democratic process, and rights I’d long believed were inalienable to me as a citizen of this smug country of mine were suddenly being stripped away. Perhaps it’s no wonder that I was drawn to female characters who sought revenge, one way or another, on the powers-that-be.

It was an awakening. I went back to my dusty manuscript with a newfound vision (and rage). I realized that I, too, was writing a female-centered thriller. My “girls” would no longer be polite and passive and pleasing to the eye. Oh no, they were going to fight. They were going to rip up the world that had created them. They were going to get bloody.

The things that I’d stripped away in my first telling—characteristics I considering unlikable—came back three-fold. My artist characters became rotten with ambition. They manipulated everyone around them, from their closest friends to their worst enemies, to further their own agendas. I set them in direct competition with each other, which allowed me to show their insecurities and jealousies, swollen to parade-balloon proportions. They made mistakes, sometimes grave and sometime petty, as I nudged their dramas closer and closer to the edge.

There has never been a way to please everyone. I, for one, am no longer willing to try.

I didn’t stop there, though. There’s a B side to the unlikability record, and it doesn’t often get played. Character motivation. In order to have a compulsively readable unlikable character, you can’t stay on the surface. You can’t have someone be bad simply to have a bad guy. That’s too easy. It will read as cartoonish. Writers need to create real, three-dimensional people, which is why we have to get inside our characters’ heads and into their pasts. We have to tunnel through their psyches to find out why they do what they do and think what they think. This is what Blake Snyder, author of Save the Cat, calls “the shard of glass:” the painful thing that affects every part of your character’s perception, but that is so grown-over she barely recognizes it anymore.

For example, if your character, like my protagonist, grew up feeling loathed and invisible, she might seek fame and attention as a (problematic) way to heal. If your character has been praised only for her appearance, she might exploit her sexuality to get what she wants. By extension then, she may feel threatened when someone usurps that power. Every good character has one—even quintessential sociopath Amy Dunne’s parents used her for profit and her husband was an underwhelming cheater—and as long as it makes sense, your reader is likely to keep reading no matter how terribly your character behaves.

Leaning in to unlikability helped me navigate my plot more effectively. It heightened the tension and conflict, and put my characters in dangerous situations they’d never have gotten into if they’d stayed pleasant. And I understand now what the push for ‘likability’ actually is—a trap. For fiction writers, and for women in general. It’s an excuse. A way to keep us flat and small and quiet. There has never been a way to please everyone. I, for one, am no longer willing to try.

__________________________________

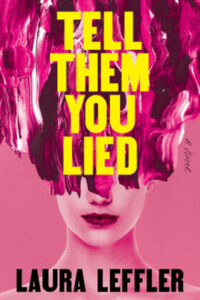

Tell Them You Lied by Laura Leffler is available from Hyperion Avenue, an imprint of Disney Books.