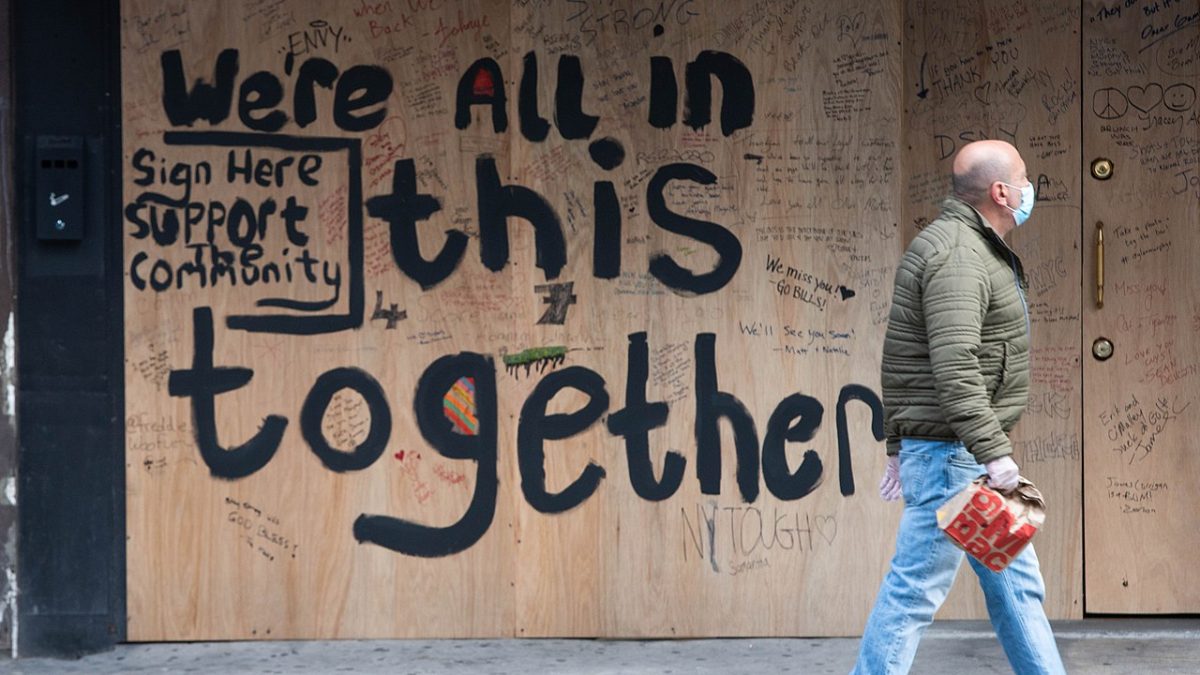

Care was everywhere—and nowhere. In the aftermath of the state’s failure to respond to COVID-19, the concept of “care” has soared to new heights, at least within the academic disciplines of disability justice and disability studies. Meanwhile, outside the academy, the pandemic was characterized by mass death, including here in New York City, the early epicenter of the pandemic in the US. The rationing of scarce resources like ventilators represented stark failures of state preparedness. It revealed the devastating free fall caused by a vacuum of care. Consequently, anyone writing about bodies, care, disability, and medicine over the last four years seemed compelled to answer the question: “What about COVID? For that matter, what about long COVID?”

While the CDC has acknowledged its existence for four decades, myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) reached new prominence in the aftermath of COVID-19. The virus is causing syndromic postviral illness at massive scale, with many cases of long COVID diagnosed as ME/CFS. Because its cardinal symptom is malaise (fatigue, dizziness, brain fog) after any form of exertion, ME/CFS impacts sociality at a fundamental and pervasive level. Sometimes referred to as the “solitary confinement disease” by the patient community, ME/CFS renders one-quarter of people living with it bed- or housebound, but their profound debility has been underacknowledged by the state, medicine, and bureaucratic systems of support.

I am an ethnographer of ME/CFS, and have studied patient groups advocating for increased ME/CFS awareness and care since 2016, four years before the pandemic. My interlocutors were some of the few people for whom the pandemic changed little about their everyday lives. After all, what is “shelter in place” or “stay at home” for someone already homebound? As restrictions were lifted, however, people with ME/CFS and immunocompromised populations remained vulnerable to COVID; even after able-bodied people “moved on,” attached to the fantasy of “returning to normal.”

The lifting of these restrictions, in other words, itself represented another abandonment by the state, as disabled activists have asserted they have been dismissed and disposed of, and people with long COVID are left in debilitating isolation. People with ME/CFS and long COVID alike form solidarities and collectives at the same time that they face the stark limits of what state and collective support look like. It is time to figure out how we can have “more care” without its coercions and inequities.

But care can mean a lot of things: It’s an affect (“I care about you”), structure (“healthcare”), and practice (“providing care”) all at once. It can contain love, create resentment, or, as disability rights activists point out, force dependency. In the context of solitary confinement, then, what kind of care is called for?

This is why COVID’s aftermath is a key context for recent books on “care.” We all needed care during the COVID-19 pandemic, but dominant narratives—that the pandemic is “over,” that there is a normal to which we can return—obscure the unevenness with which care is distributed, especially for those with postviral illness. A historical critique of hegemonic arrangements of care, Premilla Nadasen’s Care: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (2023) points the way to a less violent, non-state version of care. Authored by a group calling themselves “The Care Collective,” The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence (2020) argues we need to place care at the center of life, and lays out what kinds of material conditions we might need to get there. Finally, Akemi Nishida’s Just Care: Messy Entanglements of Disability, Dependency, and Desire (2022) is an ethnography of care labor, both in the form of US state programs like Medicaid and in the form of grassroots care collectives.

All examine care not in terms of rights-based independence models that exalt the autonomous liberal subject, but rather, by aiming to usher us into new modes of caring that are more humane, less capitalistic, and fulfill the needs of marginalized subjects who have been left behind by the state. And whether their aim is to address COVID-19 or not, all note that their books are situated in the pandemic context.

Care’s relationship to chronic illness and disability has a longer history. While the pandemic revealed a lack of care, the deinstitutionalization movement of the 1960s and ’70s revealed that violence and coercion, too, have been enacted in the name of “care.” Medical fixes aim to “cure” disabled people, regardless of what the disabled person wants. Involuntary institutionalization and care homes also demonstrate that care can justify forced dependencies. Disability rights movements in the 1970s thus emphasized the importance of disabled people’s independence. The move toward independent living—highlighting that disabled people need not be controlled under the guise of care—informed the beginnings of the field of disability studies, summed up in the “social model.” It is social conditions, rather than something wrong with the disabled person themselves, that create disability. The disabled person does not need to be “fixed” but to be free from societal constraints. The implication is that disabled people, with enough rights, can achieve full equality without the violence of confinement or social control.

More recently, disabled writers have rightly criticized the emphasis on independence, which exalts the liberal, autonomous subject as the pinnacle of disability rights. The independence model also invisibilizes care labor in favor of a rights-based model, without a critique of capitalism: Even as disabled people are not worth any less than able-bodied people, they frequently need (underpaid) caregivers to meet basic needs. To address these pitfalls, disabled activists and scholars have put forward a model of “interdependency” that emphasizes the reality that disabled people can and do need care from others—and holds that this is not such a bad thing. This care can come in the form of paid or unpaid caregivers, or from other disabled people. Interdependency reconciles the need for a new ethics of care, the recognition of unpaid labor, and a critique of the autonomous individual. The question remains, however, how this interdependency is distributed, where it might take us in the ongoing ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic, and importantly, who can achieve it.

In Care: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, Premilla Nadasen wastes no time disabusing us of romantic notions of care. Refreshingly, Nadasen does not narrowly focus on a feminist critique of reproductive labor (i.e., that the burden of care is disproportionately placed on women, or that “household labor” is treated the same as other forms of work). Rather, Nadasen actually breaks down this assumed division between household labor versus “real” labor. The monetization of care, in other words, is crucial to our current economy.

Indeed, the book’s title is a nod to Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. Nadasen chose this reference to highlight how embedded capitalism has become, if it captures even our most basic needs. While Nadasen makes this argument about our contemporary economy, she also points out we cannot have a critique of care without examining legacies of racial capitalism. “For many people of color,” Nadasen notes, “there was little distinction between production and social reproduction,” as racial capitalism extracts value from domestic workers’ bodies. She wonders if the term “care,” rather than social reproduction, characterizes these forms of labor at all. Nadasen demonstrates in detail how the concept of care can obfuscate more than it reveals. At times, Nadasen suggests we might dispense with the word all together.

At the end of the text, however, Nadasen seems to embrace the term, albeit with the modifiers “radical” and “grassroots.” Radical care, she writes, does not rely on the state, but instead “grows out of dire community need that emerges from the calculated failure of social welfare programs.” This might mean transferring care needs to community spaces and away from the state.

Nadasen provides several historical and contemporary examples of how these arrangements of care already exist, from the Black Panthers’ free meals, to disabled care webs, to street medics responding to police violence during the George Floyd protests. Nonetheless, Nadasen acknowledges “the question of whether communal care can fully meet our needs.” For instance, some people need access to medical technologies and life-saving medications. (People with long COVID may well have this concern on their minds—how can care collectives research and develop treatments they direly need for a complex disease?) The dilemma becomes who is organizing care, and under what conditions.

While Nadasen presents us with these questions, she ends by acknowledging that there is “no charter,” as of yet, that would lead us to better systems of providing for human needs. She insists, nevertheless, that it is imperative that we imagine these.

disabled activists and scholars have put forward a model of “interdependency” that emphasizes the reality that disabled people can and do need care from others—and holds that this is not such a bad thing.

The Care Manifesto stands in stark contrast to Nadasen’s arguments about the state and responses to its abdication. Written by “The Care Collective,” The Care Manifesto indicts neoliberalization and care economies, driven by profit rather than human needs. But it does not necessarily dismiss the state programs that Nadasen argues we must move away from.

In fact, Nadasen cites The Care Manifesto as an example of what she sees as too narrow a focus on “the liberal welfare state.” The Care Collective argues that we need to “put care at the very centre of life,” asking, “What kind of infrastructures are necessary to create communities that care?” While Nadasen de-emphasizes state supports, the Collective cites policy changes that might better enable people to care for one another: for example, investing in cooperative housing; rent caps; healthcare; and childcare.

These may seem like a simple revisitation of a Keynesian welfare state of yore. But The Care Manifesto does analyze how capitalism, at its very core, inherently diminishes caring capacities. Shorter working hours, for example, are “key to facilitating the conditions that can educate and expand our capacities for caring, encouraging mutual participation in democratic deliberations … of care. Once care is prioritized in this way, it becomes easier to find ways to recognize and try to meet our shifting dependencies.” Thus, it is not that the welfare state is the ultimate solution; rather, the Collective points out how state policies, in tandem with capitalist economies, restrict how we might abundantly care for one another.

What The Care Manifesto demonstrates is that we need to understand the material conditions by which forms of Nadasen’s “radical care” might become more possible. I am more inclined to start with the Manifesto’s questions rather than jump to radical care as the solution.

Under what conditions can people care for one another? How can we scale care to be noncoercive and abundant? Read alongside Nadasen, The Care Manifesto helps us through these questions. We may turn to what Jina Kim has recently emphasized, a potential synthesis of Nadasen and the Manifesto: “Dreaming of infrastructure” yokes prefigurative practice to more scalable forms of care.

It is true that not everyone can form radical care collectives if they are housing insecure or hungry. And it might not be so easy if they are too debilitated, like many people with ME/CFS and/or long COVID: because the state systematically dismisses their disease, fails to provide research funding, and denies disability insurance—something that now, under the Trump administration, millions will be lacking due to the gutting of Medicaid and slashing of medical research under the NIH. Still, while the state may not be the be-all, end-all, the Collective suggests there are basic necessities—heretofore unrealized—that might help caring communities flourish.

The division between Nadasen and The Care Manifesto boils down to classic divides between socialist, communist, and anarchist ideas over scalability, resource distribution, and technological development. In other words, what do we get from exalting prefigurative care communities, when not everyone can access them? Are autonomous communities a good way to organize needs? Finally, how do we handle more-complex care needs—such as medical technologies and the need to develop drugs and treatments—all the more urgent after COVID-19?

The pandemic, after all, did not just reveal care’s vacuum. It also demonstrated, in real time, that “care” in the first place contains contradictions and dilemmas.

These problems are not merely theoretical, as Akemi Nishida’s Just Care reveals. Through ethnographically grounded research, she describes how disabled people navigate such problems in everyday life. She provides stories of care workers (funded through state programs) as well as community-based care networks comprised mainly of disabled people.

Augmenting Nadasen and The Care Collective, Nishida’s method allows her to articulate how these tensions—between dependency and interdependence, the state and its failures—play out in the day-to-day lives of disabled people and the ones who care for them, categories that are far from mutually exclusive. Like Nadasen, Nishida highlights that caregivers are also debilitated themselves—not always self-identifying as disabled, but through the conditions of capitalism. “The larger structure of care,” she argues, “shapes these individual experiences relationally—that is, the structure in which care workers are consumed also depletes those situated as care recipients.”

Nishida provides a robust critique of the Independent Living Movement described in the opening of this piece. Simply looking to the depletion of these care workers shows independence is simply a myth. Austerity shows that the well-being of those that give care and those that receive care are bound up in one another.

After looking at Medicaid recipients, Nishida turns to care webs beyond systems of state support, which consistently (as Nadasen also shows) leave profound gaps in fulfilling care needs. These care collectives are alternatives to the state that, according to Nishida, are radically resistant to capitalism.

But a question emerges: In the absence of state support, is caring for one another enough? Moreover, following Melinda Cooper’s nuanced and provocative analysis of AIDS care networks, are such collectives resistant to or symptomatic of neoliberalism? While Nishida emphasizes the former, she is clear that her project is not one intended to justify the slashing of welfare systems, for example—nor does she idealize the care webs she describes. Rather, her interlocutors are “entangled in each other’s messy dependency.” Messiness, here, is oppositional to hegemonic systems of care and capital, at the same time that it creates a perpetual challenge.

“Crip wisdom,” a term both Nishida and Nadasen end on, is an important addition to discussions of care. “Crip wisdom” is a term disabled communities use to express how disabled people already have expertise in caring for themselves and one another. But as Nishida is clear on, having crip wisdom does not equate to giving and receiving perfect care. In fact, if there is one thing that is strikingly wise about Nishida’s interlocutors, it is how they articulate care’s shortcomings: It can fail when they are tired, when they have to work, or even when people simply don’t like them.

Being in relation to others is exhausting and inconvenient. But perhaps crip wisdom is about both the means and ends of care: how to care, but, also, how to understand care’s perpetual limits.

Under what conditions can people care for one another? How can we scale care to be noncoercive and abundant?

I return now to reflect on my own interlocutors: What would it take for them to be cared for? Can this question be answered by these texts, taken together, especially in the context of new formulations of (inter)dependence in disability studies?

People with ME/CFS may be free from confining nursing homes, but so many are confined to their own homes. Many of my interlocutors lived in suburban isolation, with husbands that did not believe them but that they had to stay with in order to have health insurance. Or else they lived alone, receiving meager payouts through Social Security,barely scraping by; they grew increasingly estranged from friends and had limited means to even leave their houses (many cannot drive due to cognitive impairment and visual disruptions). No one I interviewed lived in what Nadasen might describe as “radical care”; what the Collective describes as “caring communities”; or what Nishida describes as “care collectives.” Indeed, participating in those very organizations of social life would wear them out, making them sicker.

The reality, as Nishida points out, is that “many people are often stretched thin.” But certain chronic illnesses like ME/CFS—defined by postexertional symptoms and dismissal—only further challenge utopic visions of smooth, egalitarian interdependency. Just as independence is a myth, so too is the notion that I can always help you as much as you can help me.

Just as disability studies unpacks independence, we also need to unpack care. Two prerequisites for “care” emerge here. First, whether it be through Medicaid or care webs, care takes a certain type of person—someone able-bodied enough to do it, or a likeable, socially connected disabled person with the energy to care. Second, it takes certain resources—having time, having a job, having housing, as the Manifesto points out. Against the romance of community, we need to look at the material conditions that enable care in the first place.

Do we need better, more radical, or collective care? Yes. But if we were to take dependence, isolation, and impairment seriously, I am skeptical that “valuing care” can pull all of the analytic weight and political promise we project onto it, even as COVID-19 showed we desperately need it. Care can mean, as in Nadasen, the ways that capitalist economies absorb reproductive labor. It can mean, as in The Care Collective, ways to support the fundamental fact of dependency. Or it can mean, as for Nishida, an ethos that values disabled lives. An unproblematized notion of care—that we can just make it more radical, better, or simply have “more” of it—risks beginning as a critique of the abdication of the state, but ultimately ends up justifying that very abdication.

This abdication, along with a capitalist economy that values energy at its very core, puts many chronically ill people, especially those with ME/CFS, in a double bind: left behind and systematically denied what it would take to abundantly support themselves and therefore others. As Nishida shows us, the reality is that care is a thoroughly incomplete and uneven project. In contrast to viewing care as a means to an end, let us think about what makes care possible in the first place.

My ethnographic research took place nearly a decade before the recent, thorough gutting of healthcare under the second Trump administration’s “Big, Beautiful Bill.” Its effects cannot be overstated: Millions will die from it. The critique of state systems of support and new imaginaries of care has been one of the main strengths of disability studies and disability movements.

But if you are too sick, you do not have the energy to care for others. If you are kidnapped by ICE and stripped from your community, you cannot care for your family. If you are poor and burdened by new work requirements for welfare, you don’t have time to care. In the context of state abandonment, we have to unpack “care’s” complexities—and discursive and material limits. Care doesn’t have to be this way. ![]()