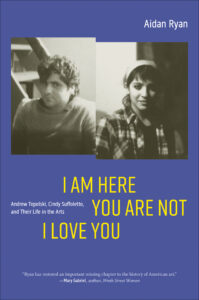

Every biography begins with a unique set of constraints: there are only so many knowledgeable sources, only so much already written about a subject, only so many boxes in the archive. Anything beyond those constraints becomes fiction. At least, that’s what I thought when I set out to write I Am Here You Are Not I Love You, a biography of the artists Andrew Topolski and Cindy Suffoletto, my uncle and aunt. Confronting those constraints, though, forced me to rethink what happens at that line between nonfiction and fiction. There is a space in the art of biography for material that doesn’t come from sources and archives. Handling it requires equal parts imagination and integrity.

Article continues after advertisement

I had the advantage of knowing my subjects personally while they were alive—but, beginning the project more than a decade after their passing, my research was limited to the scant public record and to the recollections of the surviving handful of their closest friends. Very little had been written about either of them, and there was even less in the way of diaries, letters, or digital footprints. Even more challenging: some of my sources disagreed about fundamental aspects of Cindy and Andy’s story or told me things that couldn’t possibly be true.

There is a space in the art of biography for material that doesn’t come from sources and archives. Handling it requires equal parts imagination and integrity.

As a nonfiction writer—specifically one with training in journalism—I didn’t have methods to make sense of so many doubtful, partial, or contradictory accounts. As I thought about what to transfer from my interview notes to the manuscript, I realized that the available material required a different set of tools—tools I had learned to use through my earlier training in fiction.

The most obvious example springs from a question that I couldn’t avoid answering: How did Andy and Cindy meet? As I spoke to the people who had been around them at the beginning, each had a different recollection of how it happened, ranging from meet cutes to mild scandals. I heard that Andy and Cindy met at a bar where Cindy was working, that Cindy had been Andy’s student, and that they met at three different art galleries. Some of the stories made so much sense that I started to write them into the book before realizing the details didn’t add up. I faced one of the central risks of biography—that of alchemizing apocrypha into public record. I needed a different approach.

I tried to do the ethical thing first, put all my biographer’s cards on the table, ticking through the available theories and their deficiencies.

Maybe it was this way. Or maybe another way. Maybe they’d spoken already, or maybe they’d only exchanged a few frank looks.

The truth is I don’t know.

There. I couldn’t be accused of misleading anyone. But I felt I still had to tell a story. We take the facts as far as we can. But the interesting choices come at the end of our knowing.

Ironically, the problem that my research presented—not knowing what happened to Cindy and Andy at crucial moments—was precisely the place where I preferred to work in fiction. Before I attempted this biography, I had worked on novels, but hadn’t managed to publish any. In writing fiction, I wanted to wonder what my characters would do next. That’s when the writing feels most alive. When I was able to operate in that state, I worked by paying attention to where the writing had delivered me. What does it feel like to be here in this moment, this scene, at the edge of the unfinished text? The feeling-tone of that experience—the time of day, the temperature of the room, the echo of the last thing a character said—suggests what the characters will do next.

I wasn’t able to switch immediately from third-person, journalistic nonfiction into this purely fictive mode. As an intermediate step, I treated myself as a character. I began by relating what it felt like for me to visit the actual studio Andy and Cindy had shared, a space in a former ice warehouse on Buffalo’s West Side.

I make my hands into a visor and press my face into the glass of the barn-style double doors of Essex Art Center Studio 30F. It’s sunny, bone-warm, mid-August—and about forty years after Cindy first crossed this threshold.

Staring into the abandoned studio and imagining the past was my first step beyond the contradictions of the record I had assembled as a journalist. I knew the people who would have been around at the time, the art they were making then, the events that would have been happening in the neighborhood, the most popular music on the radio that month. With all this in mind, I started asking questions like a novelist.

If Cindy had stepped into this studio forty years in the past, what would she have seen?

An artist, she notices the walls first, hung with a mix of work by different hands—nude figures, abstractions, canvases with fragments of complex systems, in oils and carbons, pencil and ink, metal and gauze, alongside Polaroids, postcards, clipped advertisements, scraps of inspiration or in-jokes.

I tried to turn on my senses next—what did it smell like, what did she hear?

…a familiar and inviting mix of sawdust, stove smoke, charcoal, wool coats, and Marlboro Reds over an unmistakable undertone of American lager and warm bodies.

The scuff of her shoes across the loose charcoal on the floor sounds like a needle dropping into a new record.

We take the facts as far as we can. But the interesting choices come at the end of our knowing.

I thought again of my research, with all its faults and absences. The available information suggested this scene took place in winter. Winter in a story set in Buffalo is a character, not a condition. How would that affect the scene?

Heads turn at the change in the air—particulates of snow pulled in with the door’s opening make it a wobbly foot-and-a-half into the cinder-block studio before evaporating in the heat from a wood-burning stove …

As I wrote, I remained aware of the possible consequences of staying too long in the novelistic mode. In nonfiction, details or dialogue that do not verifiably correspond to a subject’s experience risk obscuring or distorting deeper truths. But inventions are not always falsehoods. Inventions may fill in the gaps, amalgamizing the known and unknown into representative or gestural truths. For me, the novelistic invention of the likely texture of scenes like this allowed me to push past the limits of the material record—what happened—and access more interesting truths about what it meant to Cindy and Andy, their cohort, their environment.

Why did my research point to a romance beginning in winter? What did it mean? By writing the scene like a novelist, I realized something about how the weather in Western New York shaped Andy and Cindy, as it shapes all of us.

It had to have been a winter night.

In the summer, people here are too busy enjoying themselves—drinking on patios, reading languorous books, stretching weekends in Crystal Beach or Sherkston out over three, four, five days—to do much of any importance. Only when we’re forced inside by the weather, into our tight Queen Annes and converted studios, with the heat turned up and cold beers in the fridge and our elbows on our knees, do we experience those collisions that change the course of a life.

The book I wrote is ninety-nine-point-nine percent verified, fact-checked, and corroborated historical truth, and the parts that involve invention clearly announce themselves. But by thinking like a fiction writer, I was able to do more than merely present incongruent possibilities or dead ends. I was able to access on a deeper level the feeling of giddiness before Andy’s first show in Paris, for example, or the exhaustion on the evening of 9/11, or the intimacy of the last artworks Andy and Cindy made together. Wherever sources disagreed or there was an omission in the archive, I was able to maintain the texture of Cindy and Andy’s real life, a kind of bridge across the gap.

Did they meet on a winter night? A journalist would say I don’t know. But I’ll say maybe. Probably. Yes.

__________________________________

I Am Here You Are Not I Love You: Andrew Topolski, Cindy Suffoletto, and Their Life in the Arts by Aidan Ryan is available from University of Iowa Press.